What is preclinical Alzheimer’s disease?

What is preclinical Alzheimer’s disease?

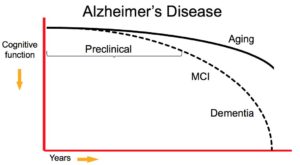

Preclinical Alzheimer’s is a newly defined stage of the disease reflecting current evidence that changes in the brain may occur years before symptoms affecting memory, thinking or behavior can be detected by affected individuals or their physicians.

Preclinical Alzheimer’s is a newly defined stage of the disease reflecting current evidence that changes in the brain may occur years before symptoms affecting memory, thinking or behavior can be detected by affected individuals or their physicians.

The guidelines defining this stage were recommended by a workgroup, consisting of experts from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association. While these guidelines identify these preclinical changes as an Alzheimer’s stage, they do not establish diagnostic criteria that doctors can use now. Rather, they propose additional research to establish which biomarkers may best confirm that dementia-related changes are underway in the brain, and how best to measure them. A biomarker is something that can be measured to accurately and reliably indicate the presence of disease. An example of a biomarker is fasting blood glucose (blood sugar) level, which indicates the presence of diabetes if it is 126 mg/dL or higher.

Researchers currently use the term “preclinical Alzheimer’s disease” to refer to the full spectrum from completely asymptomatic individuals with biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s to individuals manifesting subtle cognitive decline but who do not yet meet accepted clinical criteria for mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Why is this newly defined stage important?

Emerging data in clinically normal older individuals suggest that amyloid plaque accumulation is associated with brain changes. Therefore, the long preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease may provide a crucial window of opportunity to intervene with disease modifying treatment.

A recent report on the economic implications of the impending epidemic of Alzheimer’s, as the “baby boomer” generation ages, suggests that 13.5 million individuals will get the disease by 2050. A hypothetical intervention that delayed the onset by 5 years would result in a 57% reduction in the number of Alzheimer’s patients, and reduce the projected Medicare costs from $627 to $344 billion dollars.

Screening and treatment programs instituted for other diseases such as cholesterol screening for heart disease, colonoscopy for colon cancer, and mammography for breast cancer have already been associated with a decrease in mortality due to these conditions. The current lifetime risk of Alzheimer’s disease for a 65-year-old is estimated to be 10.5%. Computer models suggest that a screening instrument for Alzheimer’s, and an early treatment that slows progression by 50%, would reduce that risk to 5.7%.

Both laboratory work and recent disappointing clinical trial results raise the possibility that therapeutic interventions applied earlier in the disease would be more likely to modify its course. Studies with mice suggest that amyloid-modifying therapies may have limited impact once the degeneration of brain neurons has begun. Several recent clinical trials in the stages of mild to moderate dementia have failed to demonstrate clinical benefit, even with autopsy evidence of decreased amyloid plaque in the brain.

Several biomarker initiatives, including the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), and the Australian Imaging, Biomarker & Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing (AIBL), as well as several major biomarker studies in the United States are ongoing. These studies have already provided preliminary evidence that biomarker abnormalities consistent with Alzheimer’s disease are detectable prior to symptoms showing.

In other words, amyloid plaque build-up is present in the brains of the healthy individuals being studied. The number is dependent on their age and genetic background, but ranges from approximately 20-40%. Interestingly, the percentage of amyloid-positive normal individuals detected at a given age closely parallels the percentage of individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia a decade later.

What factors affect the progress of earlier clinical trials?

Research evidence suggests that factors, such as brain and cognitive reserve, other age-related brain changes, as well as other brain diseases (cerebrovascular disease or presence of Lewy bodies) may change the progression of Alzheimer’s disease symptoms.

The term “brain reserve” refers to the capacity of the brain to use its damaged resources. This may explain why a substantial number of individuals can have all of the classic signs of Alzheimer’s disease at autopsy but never experience dementia during their life. Researchers speculate this can be due to greater brain density or larger number of healthy neurons to support normal brain function.

Another layer of complexity is added when researchers look at people’s “cognitive reserve”, which refers to their ability to use alternate thinking strategies to cope with the effects of physical brain pathology. For example, researchers believe that individuals with higher socio-economic status or engagement in cognitively stimulating activities have a mental advantage.

Other health factors, such as hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes have been associated with an increased risk of dementia, and may contribute directly to the impact of Alzheimer’s pathology on the aging brain. It also remains unclear whether there are specific environmental factors that may influence the progression of the disease.

On the positive side, there is some evidence that engagement in leisure activities, including cognitive, physical, and social activity, may be associated with decreased risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Helpful information related to this post: