Dementia caregiver overcomes depression and cultural stigmas to care for her family

By Kerry Larkey, MSN, RN

Data released earlier this month from the Alzheimer’s Association® 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures report highlights the impact on depression and mental health in dementia caregivers.

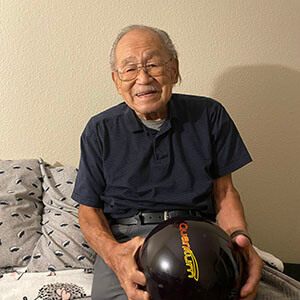

In 2017, June Yasuhara’s mother, Eiko Oka, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Two years later her father, James Oka, was told he had dementia. June immediately became the primary caregiver for both parents—a difficult task for anyone. Then, in 2020, June found herself battling depression as she continued to care not only for her parents but also her two children. June hopes the story of her family’s journey will help normalize the stigma against Alzheimer’s and caregiver mental health

Rooted in Japanese culture

Eiko was born and raised in Japan where she enjoyed a career as an opera singer and an actress in Japan. During the height of World War II, Eiko immigrated to the United States when she was 18. James, also of Japanese descent, was born and raised in San Jose, California, where he worked as an electrical engineer. The two met at a coffee shop in Japantown where Eiko worked. Soon after they married and started a family together.

Social impacts of stigma

When Eiko Oka, June’s mother, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, June was surprised but knew she’d support her father James as they cared for her mother together. However, two years later, when James received his dementia diagnosis, June found herself the primary caregiver for two parents.

As Eiko began repeating herself more often, the illness became visible to others and her isolation increased. June’s goal was to make Eiko’s life as full and vibrant as possible but was having trouble making social connections. “It was a struggle to find someone who she could relate to and be social with,” said June. “My mom would have loved being around someone Japanese and having a friend to do activities with.”

June remembers trying to set up a get-together with another woman who had recently been diagnosed with dementia. “I said to the woman’s daughter, ‘We should get a playdate together for them. I’ll never forget her saying, ‘My mom doesn’t want to be around people with dementia because she doesn’t want to see what her path will look like.’ I felt like she was saying, ‘My mom doesn’t want to play with your mom.’”

Cultural stigma

Culture, however, can also create barriers for people living with Alzheimer’s. Early on in the disease, Elko’s dementia began interfering with her desire to socialize with friends and family. “Mom would say to me, ‘I don’t know how to explain this’ while pointing to her head,” said June. “She knew something was wrong but she totally isolated herself. She withdrew.

According to the Facts and Figures report, Asian American dementia caregivers are less likely to ask outside help and formal services. “There are a lot of cultural beliefs within the Asian community. There’s a big stigma and people are very private about dementia. I’ve heard people say, ‘Don’t tell anyone but my aunt is starting to show signs of Alzheimer’s but we’re not saying anything about it.’ I think people don’t want to say anything because it’s a head thing.”

Cultural connections

As Asian Americans, tradition played a significant role in the Oka household. During their illnesses, it became more important than ever to incorporate Japanese culture into Eiko and James’ lives. “Dad bowled in a Japanese bowling league and played poker once a week,” said June. “I also wanted my mom to be around the Japanese community and for her to feel comfortable.” James continued to bowl until near the end of his life and Eiko still enjoys listening to Japanese music.

Eventually, June helped Eiko and James move back to Japantown. “The Japanese culture is very giving,” June says with a smile. “When we moved them back, I took my parents for walks every day. Japantown got to know them again and they’ve been super supportive. My parents became a fixture there.”

The move also helped June learn more about her parents’ lives. Because their long-term memory was better than their short-term memory, Eiko and James could remember details about the history of Japantown. “My dad would tell me so many stories from the past. On a walk we’d sit and have a smoothie and I would get all of these amazing stories that I didn’t know.”

The generosity and support from the community was overwhelming. “They were awesome,” June beams. “When I went on vacation several community members even offered to check on them and bring them dinner. People just did things for us and there are so many I’d like to thank.”

When Eiko was no longer able to stand, June looked to the community for help. “I asked a woman from the community center, ‘Can you make up a chair exercise routine for her?’ She did but also made it to Japanese music. That meant everything to mom. Thank goodness for this community.”

Caregiver impacts

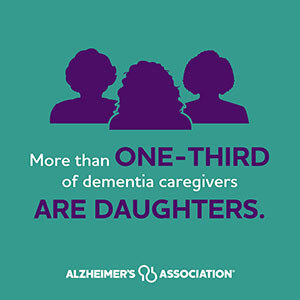

According to the Facts and Figures report, two-thirds of dementia caregivers are women. One-third of caregivers are daughters. Fifty-three percent of women with children under age 18 felt that caregiving for someone with dementia was more challenging than caring for children. Women experience higher levels of burden, impaired mood, depression and impaired health than caregivers who are men.

While caring for her parents, June was also raising two teenage boys making her part of the one-quarter of dementia caregivers who are “sandwich generation” caregivers. They care not only for an aging parent but also for at least one child, placing an extra stress on these caregivers. “I know I missed three years of my children’s lives (now ages 18 and 24),” June agrees.

Caregiving can be an emotionally draining role, this was especially true for June. “Being their primary caregiver affected me tremendously,” said June. “My physical health was great, honestly, but mentally it was very emotional.”

By the end of the third year of caregiving, June fell into a deep depression. “I suffered a really bad bout with depression anxiety and became suicidal. I have generalized anxiety disorder and this was the most brutal episode because it was real. It all snowballed into worry, worry, worry. I suffered a lot.”

Mental health and caregiving

Seventy-four percent of dementia caregivers reported that they were “somewhat concerned” to “very concerned” about maintaining their own health since becoming a caregiver. Dementia caregivers have twice the odds of experiencing an overnight hospitalization than non-caregivers.

Fifty-nine percent of family caregivers of people with dementia rated their emotional stress of caregiving as high or very high and, like June, are more likely to experience depression and anxiety than non-dementia caregivers. This is especially true for the Asian American community. The Facts and Figures report highlights that Asian Americans have greater care demands and experience greater depression compared with White caregivers.

June falls into the 44% of dementia caregivers who have depression. The prevalence of depression is 30% to 40% higher in dementia caregivers than other caregivers. Dementia caregivers in the United States are more likely to have experienced depression (32.5%) or anxiety (26%) when compared with dementia caregivers from other countries.

Finding help

“At first, I didn’t realize how much it takes to take care of someone with Alzheimer’s,” June says. “There are some cultures where they won’t go outside of their family to get help. I would get mad when people said I needed help because I felt like I knew best and would follow through. I was worried that if it’s a job someone might cut corners.”

To her own surprise, everything changed for June in 2020 after she decided to find help. From the depths of depression, she arranged for two professional caregivers to provide in-home 24/7 care for Eiko and James.

Now June chuckles while admitting, “The caregivers take way better care of them than me. And yes, it’s their job but they love it. They love my mom so much.” June now has peace of mind and can sleep without worrying. “One [of my parents’ ] caregivers loves Japanese culture and speaks a few words of Japanese,” June continues. “The other tries to cook Japanese food.”

With the caregivers involved, June was able to address her depression and found herself with time to just be a daughter to her mom. “Now if someone offers me help, I will take them up on it. I realized it’s better for my mental health overall.”

Raising awareness

Throughout her time as a caregiver, June realized there was more she could do for the Japanese community. She now spends her time volunteering with the Alzheimer’s Association. Currently June is a member of the Japanese American Advisory Council and a community educator, both of which help bring resources and awareness to the Japanese community.

To decrease stigma, June thinks it’s important to educate and inform others in her community about Alzheimer’s. “I think being vocal about it helps,” said June. “The big thing for people to know is that dementia isn’t their fault. It’s not under their control.”

Increasing awareness also helps the community to connect with the person living with dementia. “I think people don’t talk about it to protect their loved ones from being treated differently. But really when someone comes across a person with dementia and they are speaking like they need more patience, if the person knows they have dementia they will have more patience.”

Not only does June help educate her community, she is also an Alzheimer’s Association advocate. She uses her personal story as a way to encourage members of congress to fight for critical Alzheimer’s research and care initiatives at the state and federal levels.

Connecting with others

June encourages all caregivers to find support wherever they are able. “I believe it’s important to talk to someone who is going or has been through what you are going through,” said June. “It’s really a comfort to have someone to relate to. It helped me to chat with a friend every night about what we went through with our parents that day.”

Although the journey was filled with ups and downs, today June describes her experiences as a caregiver with joy and humor. She is incredibly grateful to the Japanese community and the professional caregivers for the positive impacts they had and the lives of her parents. “Now my mom does not talk and she is in a wheelchair,” June says, “and she’s having a blast and living the best life she can! Ten or twenty times a day I say how lucky I am.”

It can be overwhelming to take care of a loved one with Alzheimer’s or other dementia, but too much stress can be harmful to both of you. If you are experiencing symptoms of stress or depression know that you aren’t alone and help is available. Learn more about caregiver stress and depression.

Facts and Figures is an annual report released by the Alzheimer’s Association. It reveals the burden of Alzheimer’s and dementia on individuals, caregivers, government and the nation’s health care system. Download your copy and learn more at alz.org/facts.

Check out our website to learn what the Alzheimer’s Association is doing to address health disparities and provide support for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders living with Alzheimer’s or other dementia.