History of dementia inspires San Francisco resident to keep his brain healthy

Bill Brees first realized he was at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease when his father, Walt, died of the disease at age 84. In 2021, also at the age of 84, Bill’s brother Bob died of Alzheimer’s. Statistically, that puts Bill, who is now in his 80s, at a higher risk of developing the disease himself. Taking his health into his own hands, Bill signed up for a brain health study through UC San Francisco (UCSF). Bill has successfully made changes in his life to reduce his risk of developing Alzheimer’s, now he helps others do the same by sharing what he’s learned.

Helping from afar

Bill moved from San Diego to San Francisco in 1985. When Walt, who had remained in San Diego, first began showing symptoms in the late 80s, Alzheimer’s disease wasn’t something that was discussed as widely as it is today. This was especially true when it came to discussing the impact the disease had on family and friends.

Understandably, Bill’s mother Jean found it difficult to grasp what was happening with Walt. Jean would sometimes get angry or annoyed with Walt’s lapses in memory and judgment. Accepting that Walt was having any cognitive problems was threatening to her, and according to Bill, “After 60 years of marriage, old habits die hard.”

“She couldn’t really grasp the concept that he wasn’t able to function,” said Bill. “She would berate him, saying ‘Why don’t you do this or that?’ He couldn’t answer. He didn’t know why. But little by little, the truth soaked in and she was able to calm herself and return to being the supportive partner she always had been.”

When Walt was in the late stages of the disease, needing to be bathed and fed, it was discovered in a routine doctor visit that he had colon cancer. “My mother was totally overwhelmed by that discovery,” said Bill. “He was admitted to the hospital and within days developed pneumonia. I encouraged her to discuss treatment options with the professionals. She did, and as difficult a choice as it was, we decided as a family not to treat the pneumonia.

“We couldn’t put him through cancer treatments that would scare him and not even add quality of life if they were effective. We moved him to a nursing home and he died peacefully under sedation three days later.”

Participating in research

In the late 90s, Walt had been a participant in an early UC San Diego study on Alzheimer’s. Several years later, when Bill learned of the UC San Francisco Memory and Aging Center (UCSF MAC) study of healthy aging, he decided to follow his father’s lead and sign up.

“Knowing I had a family history [of Alzheimer’s], I wanted to do something that would aid research, exactly like my father did years earlier. [Clinical trials are a way] of passing it down through generations so my two adult children and five grandchildren can benefit from it,” said Bill. “It’s almost 99% painless, so why not?”

Smiling, he goes on, “I also get bragging rights by participating in experiments and going through MRI and cognitive testing frequently. Not everyone is going to volunteer for an MRI or call TrialMatch® and find a trial.”

Clinical trials are research studies conducted with human volunteers to determine whether treatments are safe and effective. Without clinical research and the help of participants, there can be no treatments, prevention or cure for Alzheimer’s disease.

As a cohort of UCSF’s study, Bill is one of many volunteers helping find diagnostic tools, develop treatments, and helping to one day find a way to prevent Alzheimer’s and other dementias. He sees this as a contribution to other families facing this disease.

“This is no different than any other volunteering,” said Bill. “It’s something that is important to me personally. I do get something out of it myself, too. It reduces my anxiety about what’s going on in my body. I’m constantly being monitored at a professional level. Even though it’s a ‘blind’ study and I never know results. But, if they find anything that needs treating, they’ll ‘take the blinders off’ and tell me.”

Volunteering

As a participant in the clinical trial, Bill is able to attend an annual symposium of different presentations hosted by UCSF MAC where researchers present their most recent findings. Bill said, “After a presentation one year by the Alzheimer’s Association®, I talked to the presenter and put my name down to become a volunteer and went from there. Teaching something is the best way to learn it.”

Bill has an interesting history of different kinds of volunteering. In addition to being a STOP AIDS educator in the early 80s where he facilitated “Safe Sex Workshops,” he was also involved in a local church that welcomed members of the LGBTQIA+ community who were not welcomed by their previous churches.

Bill served on the board and also as the representative for the church at the San Francisco Council of Churches. He went to South Africa to train others in retreats and group facilitation. Currently he spreads his volunteering time between the Alzheimer’s Association, facilitating groups of high school foreign exchange students coming into the United States, and judging the efforts of kindergarten through high school young people in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) robotics tournaments.

Volunteering with the Association

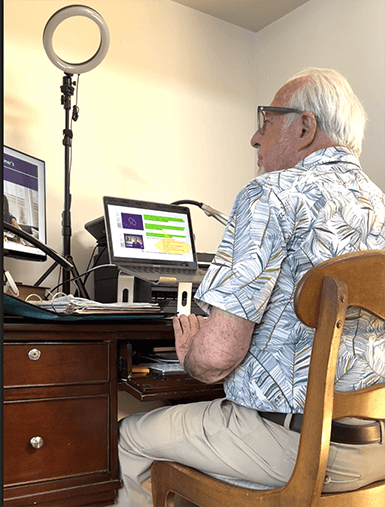

Bill began doing presentations as a community educator for the Alzheimer’s Association in January 2021. He delivers programs not only to the LGBTQ community, but wherever the Alzheimer’s Association needs him.

“I’m retired, and I balance my time these days between self, family, friends and community,” said Bill. “Volunteering for organizations that help people – young or old – is important to me. I chose the Alzheimer’s Association as one of those. Being retired, I really do like to stay active and connected, and the time I allocate now to help others learn about this disease and promote the search for a cure fits into my personal schedule easily.”

A brother with Alzheimer’s

Less than four years ago, Bill’s older brother Bob, who lived in Washington, began to show signs of dementia. Bill and Bob spoke on the phone every month. As they expected, they both began to notice the changes Bob was showing in his memory and focus. Luckily, since Walt’s death, information about Alzheimer’s and dementia had increased and Bob, a pilot and avid sailor, understood the course he was on. They both joked about it and tried their best to focus on the present.

Bill did his best to share the information he had learned through the Alzheimer’s Association with Bob’s wife. “She was getting advice from her daughters and from me,” said Bill. “She was in the middle, and it was a difficult negotiating stance with my sister-in-law. I learned long ago there are a lot of people who need help, fewer people that want help. You have to find that line, you can’t keep hitting your head against a brick wall.”

Like his father, Bob was also diagnosed with colon cancer in his early 80’s. Since he was still cognitively aware at that time, he chose to treat it aggressively. Bob and his wife were able to continue living together at home with her as caregiver until he died in the middle of 2021.

LGBTQ and Alzheimer’s

The LGBTQ community may face particular challenges related to Alzheimer’s and dementia, including finding inclusive and welcoming health care providers, less ability to call upon adult children for assistance, concerns about stigma and higher rates of poverty and social isolation.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association and SAGE, 7.4% of the lesbian, gay and bisexual older adult population is living with dementia. Forty percent say their support networks have become smaller over time. Additionally, 40% also say their health care providers don’t know their sexual orientation for fear of discrimination.

In another document prepared by the Alzheimer’s Association and SAGE, Issues Brief: LGBT and Dementia, one in five LGBT people become caregivers at a higher rate than the general population. Many LGBT older adults may not have a relationship with their legal or biological families and are instead supported by their families of choice.

As LGBT people age, these chosen family members, friends and community members often serve as caregivers. Since LGBT elders are less likely to have children to assist them and more likely to be single, adult children and partners often are not part of the caregiving mix. As a result, caregivers of LGBT older adults may be a similar age as the person for whom they are caring.

“We need to be aware of any special factors in every ethnic, cultural, age, gender, and other group’s risks and care realities,” said Bill. “Certainly, the LGBTQIA+ community has some unique differences. But other groups have theirs, too.

“Getting the message to these groups may benefit them. [Alzheimer’s Association] presentations get that message out there so that others may benefit from it. People of all groups that have special risk factors are needed in research studies. It’s vital to make sure treatments are found that match any special needs of a group if they don’t respond to ‘mainstream’ treatments.”

Keeping his brain healthy

Researchers believe there isn’t a single cause of Alzheimer’s disease. It likely develops from multiple factors, such as genetics, lifestyle and environment. While some risk factors — age, family history and heredity — can’t be changed, emerging evidence suggests there may be other factors we can influence.

Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits. Combining these habits will achieve the maximum benefit for the brain and body. It’s never too late or too early to incorporate healthy habits.

Because of his increased risk, Bill has taken this to heart and focuses on the factors he can control, like those found in the 10 ways to love your brain. Here are few things Bill has changed to help keep his brain and body healthy:

- Eating a healthy and balanced diet that is lower in fat and higher in vegetables and fruit.

- Engaging in regular cardiovascular exercise that elevates his heart rate and increases blood flow to the brain and body.

- Staying socially engaged.

- Challenging and activating his mind.

“My nutrition, fitness routine and strength training support [the activities I like such as] hiking, SCUBA diving, river rafting, zip lining and other outdoor activities. I also meditate and I’m currently learning Arabic,” said Bill. “Even small things, like playing a new and challenging board game with my 8-year-old grandson.

“I believe the doctors when they say that there are benefits to healthy living. The researchers in my UCSF study have said every doctor on this team is working out every day. If my doctor is doing it, I’m doing it.”

Find out more about resources in the LGBTQ community by visiting alz.org/lgbtq.

By participating in clinical research, you can help to accelerate progress and provide valuable insight into potential treatments and methods of prevention for Alzheimer’s. Learn how you can help find a cure by signing up for TrialMatch at alz.org/trialmatch.

Learn more: